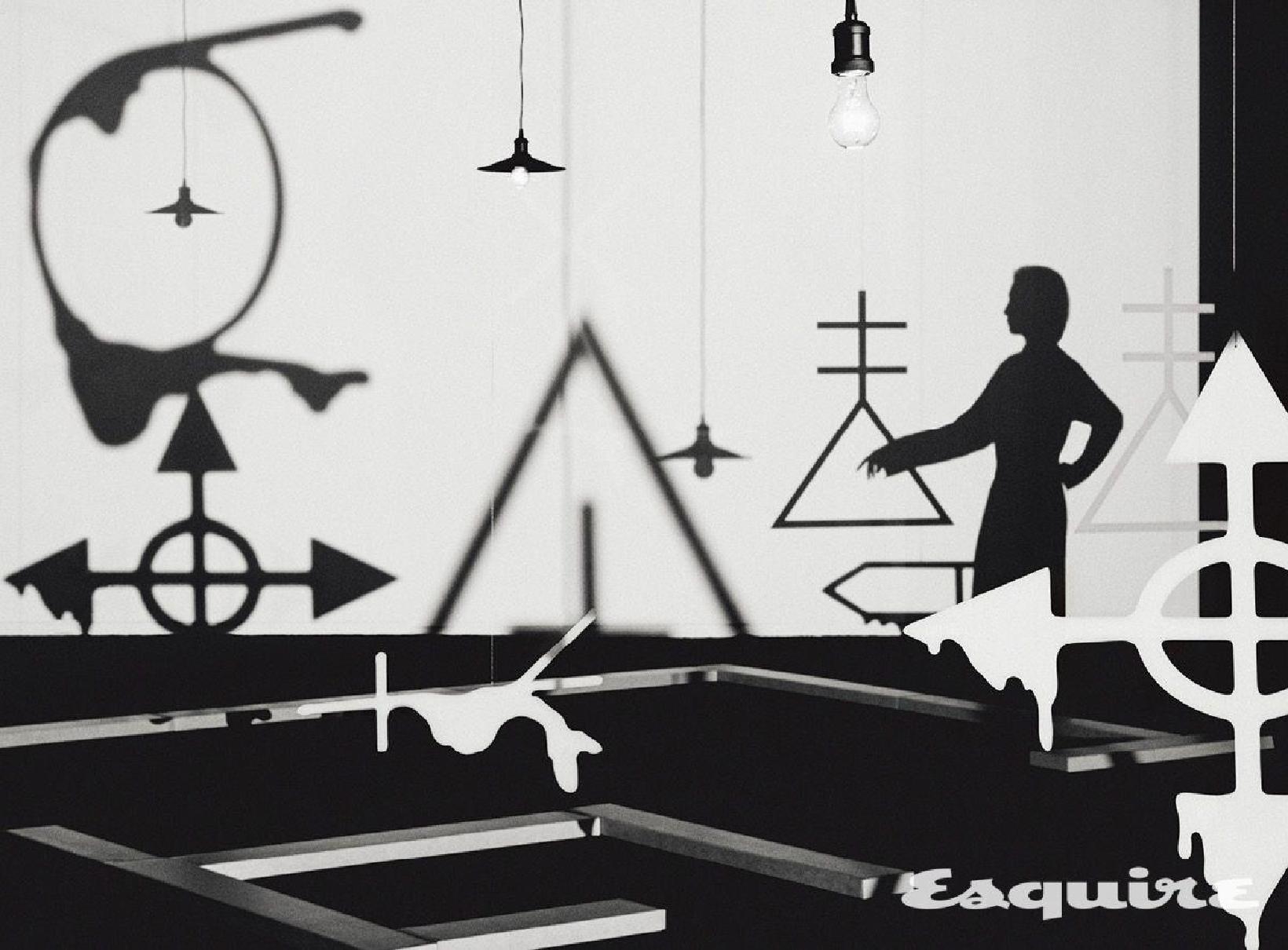

Ayoung Kim’s Incantations, from Artificial and Fictional Worlds

Recipient of the LG Guggenheim Award and the star of an upcoming large-scale façade installation at M+ in Hong Kong, Ayoung Kim sat down with Esquire to discuss what she summons from artificial worlds.

Esquire: You were announced as the first Korean recipient of the LG Guggenheim Award earlier this year, followed by exhibitions Many Worlds Over at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof in February and Plot, Blop, Plop at Atelier Hermès in March. You must have been busy!

Ayoung Kim: I visited Linz, Austria, last month to jury Prix Ars Electronica, and hopped over to the Culture Summit Abu Dhabi. Afterwards, I traveled to New York for a walkthrough of the space at MoMA PS1 where my solo exhibition will open this coming November—and perhaps most importantly, I was honored at the award ceremony for the LG Guggenheim Award. I will be debuting a new performance at the Performa Biennial in New York in November, so I also oversaw discussions on the piece and a test rehearsal while I was in the city.

Esquire: Is your upcoming work for the Performa Biennial at the extension of your Delivery Dancer series?

Ayoung Kim: That’s correct. I plan to invite two stunt actors from Korea to motion capture live in New York. When actors in motion capture suits perform a string of movements, they are directly translated into movements of Ernst Mo and En Storm (two protagonists of the Delivery Dancer series) within the game engine. After scouting for locations, we found a warehouse-like site near MoMA PS1 in Queens with an expansive area and height. We are inviting Chai Kim as the action director, who was among the team behind Squid Game as the body double for actress Jung Ho-yeon. She is a rare woman action director and incredibly talented. I worked with her once before, and I had a blast.

Esquire: She directed the rooftop fight scene?

Ayoung Kim: So you’ve seen. The scene is part of Delivery Dancer’s Arc: 0° Receiver, a horizontally long, three-channel video installation, which hasn’t been exhibited in Korea yet. She (Kim) choreographed the action sequence where three women battle to the death on a rooftop.

Esquire: I was pleasantly surprised by that scene. The characters looked like they were punching each other in real footage.

Ayoung Kim: (laughs) Yes, they show off some smash and spin kicks. One European curator who saw Delivery Dancer’s Sphere reviewed it as “an action film, as well as a work of speculative fiction and social critique.” Reading that, I looked back at my own work in realization that “oh, it could come across as an action film”—and thought, why not try a real action piece? When I did, it turned out to be really fun even though I wasn’t performing the scene myself. It was a stressbuster, even! (laughs) The live action scene features a character called Shadow Definer along with Ernst Mo and En Storm, and I was captivated by actress Hannah Geum who brought the role to life.

Esquire: Ernst Mo and En Storm’s fight appeared noticeably sexual.

Ayoung Kim: That was my intention. I wanted to convey the sense that the characters in this world, whether they be allies or enemies, are entangled in sexual tension. The fierce battle with Shadow Definer was similarly suggestive.

Esquire: I first discovered your works when I visited the National Asia Culture Center (ACC) during the Gwangju Biennale last year. I was on a tour with a group of foreign reporters, and I remember they were left in awe after watching Delivery Dancer’s Arc: Inverse and kept asking, “Who is Ayoung Kim?”

Ayoung Kim: That was an eventful time. It was exposure at that exhibition that laid ground for my upcoming exhibition at MoMA PS1, and I imagine the work that received the ACC Future Prize also played a big role in my selection for the LG Guggenheim award. So many museum directors kindly posted the exhibition on their Instagram, that even industry figures who didn’t have a chance to visit in person knew well about it.

Esquire: You were invited to the Atelier Hermès exhibition through the success at ACC, as well?

Ayoung Kim: No, but I think Soyeon Ahn (director of Atelier Hermès) has a keen intuition. She proposed the exhibition between last spring and summer, which was before the ACC exhibition. In addition, she suggested making something akin to my early research-based works, something closer to our reality, since my Delivery Dancer series and other futuristic, speculative fictions have already been on a steady trajectory. That’s never easy—for an artist to intentionally distance from a major track of their work to explore different paths. I did have strong aspirations to start, at least at some point, a project on the “oil money” in Saudi Arabia and the Middle East where my father worked for a long time. But I wasn’t sure whether turning back almost a decade was the right thing to do, especially when the Delivery Dancer series was gaining so much traction. I needed to work up a good amount of courage.

Esquire: The history of the Al-Mather Housing Complex in Saudi Arabia, where your father was dispatched as an employee of Hanyang Construction, and the development of Middle Eastern “oil money” interweave in your Al-Mather Plot 1991, which was the centerpiece at Plot, Blop, Plop. At the exhibition opening, you told me: “I want to maintain the Delivery Dancer series and my research-based works as two concurrent tracks.” Yet, I felt that the two groups were not disparate but rather two different answers to an existential question. For instance, Al-Mather Plot 1991 ends with a narrated voiceover: “In some world, my father is still wandering the desert, forever lost in the Khalas sandstorms. Something remains there forever.” It felt like a skeptic’s efforts to uncover the reason behind our existence in the world.

Ayoung Kim: That’s a fascinating take. I think I got goosebumps! (laughs) I’m grateful that you see it that way, although most audiences pay more attention to the form, topic, and visuals—some even say, “it looks like the work of a different artist.” But the works we are discussing are, within my own vision, all linked. They are mutually connected in a single trajectory.

Esquire: I agree that much of your work is interconnected. For one, the thematic interest in petroleum that embarked with Zepheth, Whale Oil from the Hanging Gardens to You, Shell continues into the issue of mobility illustrated through delivery riders in Delivery Dancer. As the exhibition catalog mentions, petroleum is the power that enabled modernism as well as the source of physical movement and speed.

Ayoung Kim: It was precisely eleven years ago that I decided to undertake the research. Studying in Europe, my thoughts kept returning to the tragedy of Korea’s modernity—and how Europe currently dominates even postcolonial discourse that deals precisely with the cultures that European powers colonized. Whether it was inspired by self-reflection or sparks of neo-colonialism, they were aware of the importance of this discipline. On the other hand, Korea’s modernity has been barely archived and remains a jumbled chaos. At the end of my own research into Korea’s modernity, I rediscovered my family’s own story. Why was my father away in Saudi Arabia and Kuwait for a decade? I never questioned this when I was young, but it started occurring to me as an adult. I sat my father down for a few days and asked him questions whenever we had time, and in between spoonfuls of food over meals. Where my father’s memories were minutely lucid, I wrote them down. The hefty record from these “interviews,” in addition to literature surveys and archive records I found at the National Archives of Korea, grew into the sound-based Zepheth series (performances and sound installations starting in 2014). I originally intended it to be visual, but I could not figure out funding. After all, visualizing one’s imaginations on the computer through 3D, motion graphic, and game engines only became practically possible in the mid-2010s—which is when I started creating speculative fiction. While producing Al-Mather Plot 1991, I realized that my collection of research materials amounted to a kind of documentary or essay film. I personally don’t really enjoy making essay films. The under-produced aesthetic doesn’t appeal to me much. (laughs) So essay film had remained at the bottom of my list, but I found the opportunity to explore it this time. I invited my father again, whose memories had faded a bit compared to ten years ago—to talk, do 3D scanning, and translate our family’s stories into archival material. Some of this naturally became a bit cringey, which was the most difficult element of the project. I have a lot of reluctance to being sentimental. I found myself clenching my teeth at some points during editing.

Esquire: Well, sentimental is good. I definitely shed a few tears. I watched the video a couple more times, and looking up the background of the Al-Mather housing complex allowed me to understand different sides to the story. For example, Riyadh was only two decades into being the country’s capital at the time of Al-Mather’s construction. So Al-Mather was a kind of “Tower Palace” (luxury apartment complex in Seoul) in the middle of a brand-new capital city.

Ayoung Kim: Al-Mather had no residents for a while and became occupied by Kuwaiti people upon Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. Then and now alike, Kuwait has been a wealthy country that produces an immense amount of petroleum in proportion to the population. I initially left out this context in the video but made the decision to include it later in the process, because I feared that once the video stated, “Kuwaiti refugees lived in the complex,” audiences will imagine the apartment as a refugee camp where deprivileged people came to stay. Which is far from the truth. The apartment was more of a hideaway where the wealthiest of the wealthiest Kuwaitis came to escape the war.

Esquire: Tracing how far the roots of this work go back, we witness how a thematic subject develops and transforms within an artist’s oeuvre.

Ayoung Kim: Counting from the beginning of the Zepheth series, it’s been around eleven years.

Esquire: During that extended time, I notice two main keywords repeating across your works: “bitumen” and “ark.”

Ayoung Kim: Exploring the question “why was my father working in a foreign country for ten long years?”, I came to the conclusion that Korea lacked petroleum, the essential driving force behind modern history. Korea always relied on imported oil, and with the oil shock, it had to raise more funds to import it—which is why it dispatched workers to the Middle East since President Park Chung Hee’s era. This led to my research on the longer history of petroleum as a substance, and I found that it appears throughout the bible, Quran, and Epic of Gilgamesh.

Esquire: Myths from that region almost always feature a figure comparable to Moses.

Ayoung Kim: In the scene where baby Moses is placed in a basket and floated down the river, the basket was “daubed with bitumen.” This bitumen is in fact a byproduct of petroleum. The description of Noah building his arc similarly references various byproducts of petroleum including bitumen, as well as petroleum in gas, viscous liquid, and solid form. The great flood also appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh and Quran. I realized that it was only when petroleum was rediscovered as a source of energy that it sparked so much war and conflict in throughout the 20th century. Petroleum is a strange substance like that, controlling politics and economics of the 20th century as if it has a will of its own. There is a work of fiction that took this approach: Reza Negarestani’s theoretical fiction, Cyclonopedia. In this book, petroleum is a demon set forth as a curse from an ancient Iranian family. The demon is depicted as swimming through porous space to puppeteer the politics of this planet.

Esquire: That’s impressive, really…

Ayoung Kim: I know, and if you think about it, it’s not far from the truth. It’s as if a sense of self resides in petroleum and we are simply its instruments.

Esquire: And how about the symbol of the ark appearing three times across your works?

Ayoung Kim: So there’s the Zepheth series and In This Vessel We Shall Be Kept. What’s the other one?

Esquire: I thought of Al-Mather itself was an ark. An ark built from the oil money of Kuwait.

Ayoung Kim: Wow, I hadn’t thought of that before. But you’re right, it was an ark full of refugees. This is an important narrative: refugees, escape, ark!

Esquire: It seems like you not only featured the ark intentionally but also held its significance at a subconscious level.

Ayoung Kim: When I collaborated with Opéra national de Paris for In This Vessel We Shall Be Kept, I examined every corner of Palais Garnier in reference to the blueprint. The building could not help but be compared to an ark. There was a lake in the basement level that provided the motif for Phantom of the Opera, and the structure was basically floating on top of it. Like Cheonggyecheon in Korea, the body of water was covered with a lid which then supports the building. Paris has an infamously weak foundation, so the builders kept experiencing flooding while laying the foundation. Unable to stop it, they eventually blocked the water with bricks layered with bitumen, which became the underground artificial lake. All of this was deeply intriguing for me.

Esquire: I often notice the rigorous scientific research supporting many of your works.

Ayoung Kim: Science is an area I am always enthusiastic to learn and to be advised on. Especially when I was working on Delivery Dancer’s Arc: Inverse and 0° Receiver, I borrowed the concept of the infinitely divisible labyrinth from Leibniz.

Esquire: Isn’t it from Borges?

Ayoung Kim: I also read of the labyrinth for the first time in Borges’ collection of nonfictions. Borges was fascinated by Leibniz’s infinitely divisible labyrinth and Zeno’s paradox, evidenced by his numerous essays. The ending of his short story “Death and the Compass” describes Leibniz’s labyrinth which is a single straight line. I was engrossed by the idea and referenced it in Delivery Dancer’s Sphere in En Storm’s line at the end: “When you go from pickup site A to destination B, you have to pass through a middle point C along the way. To reach C, you have to pass through D, a middle point between A and C. There are countless intermediate sites like that ... you will never reach point B.” This was my homage to Borges, as well as an homage to Zeno’s paradox, and at the end, also an homage to Leibniz. I often think that modes of interpretations on science can stretch towards literature and philosophy. So, I like to seek advice from researchers in the sciences, in physics, astrophysics, and mathematics.

Esquire: I also remember the line: “time slows down every time I meet her.” It was reminiscent of Einstein’s theory of relativity. I interpreted it as En Storm and Ernst Mo inhabiting different worlds in the multiverse, each racing at light-adjacent speed through routes that escape normative time, arriving at an experience of their universes merging like a wormhole.

Ayoung Kim: That’s a great interpretation. I’m fully behind it—I hadn’t thought that far anyway! I don’t really follow logic when I write scripts and fiction. Adhering to logic ironically creates more holes. Leaving holes as vague as they are, and letting audiences’ imaginations fill them, makes for a much more enjoyable approach.

Esquire: Although, I see your recent works like the Delivery Dancer series and Al-Mather Plot 1991 have achieved concrete logic. As if the holes have been somewhat filled.

Ayoung Kim: That’s one of my conundrums nowadays: for my works to remain within a fertile zone of indeterminacy, they need more holes and inexplicable elements to leave room for audiences to think, intervene, and participate. Yet, as the narrative becomes more compact, it counteracts these gaps—because a linear narrative starts to emerge. If the comparison was between poem and long-form fiction, I prefer novels, you know. But in the realm of contemporary art, I believe a work of art should contain the infinitely expandable potency of poems that transcends time.

Esquire: The project statement from your first work, Ephemeral Ephemera (2007-2009), questions: “Eventually, one realizes that the reason for existence and pursuance of life is nowhere to be found. But, is there truly no such reason?” I wonder if you create artificial worlds in pursuit of an answer.

Ayoung Kim: That’s a cool take. Do you, personally, feel connected to that sense of futility?

Esquire: Me? I believe literature—and art—was invented in response to that futility. Unable to find answers in reality, we invented a mode of play that generates answers from manmade worlds, which are symbolic worlds, and from the characters we create.

Ayoung Kim: Personally, I make art because there is no path to overcoming that sense of futility. Without permanent meaning, I see my efforts as ephemeral, as transient. There isn’t anything inherently meaningful, but I made myself move forward with things that I imbued personal meaning to, reacting to the set of stimuli that constitute our world. I create art based on that reaction. This is the way I comprehend the world, and my mode of existence that carves out a small place for me in this world. But as I continued working with this approach, I started returning less to the futility. Back when I was working in design, I was stubbornly pessimistic, thinking along the lines of “why do we live on, anyway?”. I’m so relieved that continuing to work as an artist eased my pessimism over time.

Esquire: What a relief indeed. For me it was the fact that En Storm and Ernst Mo, “doubles” as they often appear in literature, meet and coexist through minute fissures in parallel universes. That conclusion came across as a gesture of self-love: care towards the self with all its feelings of futility.

Ayoung Kim: That’s right. (laughs) Delivery Dancer is not the first time I dealt with the narrative of “doubles.” The Porosity Valley series also foregrounds this motif. The first part, Porosity Valley, Portable Holes, has a scene where a lump of metal called Petra Genetrix meets its other self duplicated through the data center and merges with it. That work, of course, also reflects empathy towards the self, which is mirrored in the feeling of consolation and love in Delivery Dancer’s Sphere.

Esquire: How do you think Delivery Dancer will evolve from here?

Ayoung Kim: I’m not sure. (laughs) This year, there are two upcoming projects in the Delivery Dancer series: the series will be unveiled early October at the 110m-high M+ façade in Hong Kong, co-commissioned with Powerhouse Museum in Syndney. The other is the motion capture-based performance debuting at the Performa Biennial. It is set in a mazelike shopping mall one often encounters in Asia, like in the Lotte World Mall, where three Ernst Mos will battle each other for survival in a delivery contest in an acrobatic action sequence.

Esquire: Wow, I can’t wait to see it.

Ayoung Kim: The crazed speed of the work is almost hysterical. There are not many lines, since it’s a façade, and I focused on the video itself.

– Editor : Park Sehoi, Photographer : Siyoung Song