*글 하단의 '한국어 텍스트 다운로드'를 클릭하면 원문을 확인할 수 있습니다.

How do you feel about reproducing the work of the 1970s at Gallery Hyundai in 2018, after 40 years?

Some of my work in the 70s has been reproduced occasionally in galleries and museums. However, there were many times that I felt unsatisfied with the space or environment due to the conditions of exhibitions that were unsuitable for my work. Thanks to the suggestion and consideration of Gallery Hyundai, I am exhibiting installations and process-oriented works that can be reproduced. This is the first time that I am reproducing my work so intensively, but I want to strive to make a solid exhibition with proper placement of works. It’s been a long time since I have created the works, but I have a lot of interest and expectation about what kind of experience they will provide to the audience and myself as well.

The title of the exhibition Disappearance is also the title of your work that was shown at your first solo exhibition at Myong-Dong Gallery in 1973. Why was the work titled as ‘Disappearance’?

The term, ‘disappearance’, still remains to be very desolate to me. I was raised to appreciate art under a particular education system of an ‘ivory tower’ (the term refers to an educational environment of intellectual pursuits disconnected from practical concerns of everyday life) whereas the nation and society were in difficult state. I was very much fortunate to be given an opportunity to have my very own solo exhibition at the only contemporary art gallery at that time in Seoul, which I have turned it into a bar. And I am pretty sure, it must not have been a pleasant experience for general audience. Back then, I was a young man who just left the ‘ivory tower’ living out of an ideal dream, painting in teal, confronting myself with the real world in grey. And I reminisce this grey world to be a place where it was shrouded in fog, feeling as if I was floating up in the air, getting lost heading back home.

You are known to have organized the artist group ‘Chungwoon’ and curated exhibitions while in high school. In other words, it is no exaggeration to say that you have been focusing on making work for over 60 years. In you long career as an artist, what meanings do you seen in your work of the 70s?

As I mentioned earlier, looking back at my memories, the world was beautiful and full of dreams for me when I was young. However, I think that it was difficult to adapt to the society after I graduated from the university. All of the works that I had been easily continuing for a long time turned out to be a dance to other people’s music while mimicking the Western art in the end, and they were in vain. Luckily enough, in the late 1960s, there were flourishing movements of free and innovative artistic forms that broke free from buildings in many countries including the United States and bold actions such as happenings and events. I think that we were realizing that it was reckless and irresponsible that we had been stimulating and mimicking the Western art with our sensitivities after the young people in the West had realized new forms through discussions every year. At that time, the art scene was changing to become a place where we could actively and freely express any kind of form and bold ways of thinking. Discovering a gap with potential there, I think my generation was thrilled to examine the new art. I remember that it was a period when I was able to have the courage to experiment with bravery and boldness and even with honesty without perfection. I thought that I should realize an artistic format suitable for myself as a young man living in Korea, and artistic forms should be able to communicate with the world.

Unlike other performance art pieces at that time, Disappearance was completed with the participation of the audience. It was an artwork that overturned the boundary and position of the artist and the audience. What triggered you to present such a performance art piece? It is believed as a very meaningful work for both Korean art history and also for you as an individual artist.

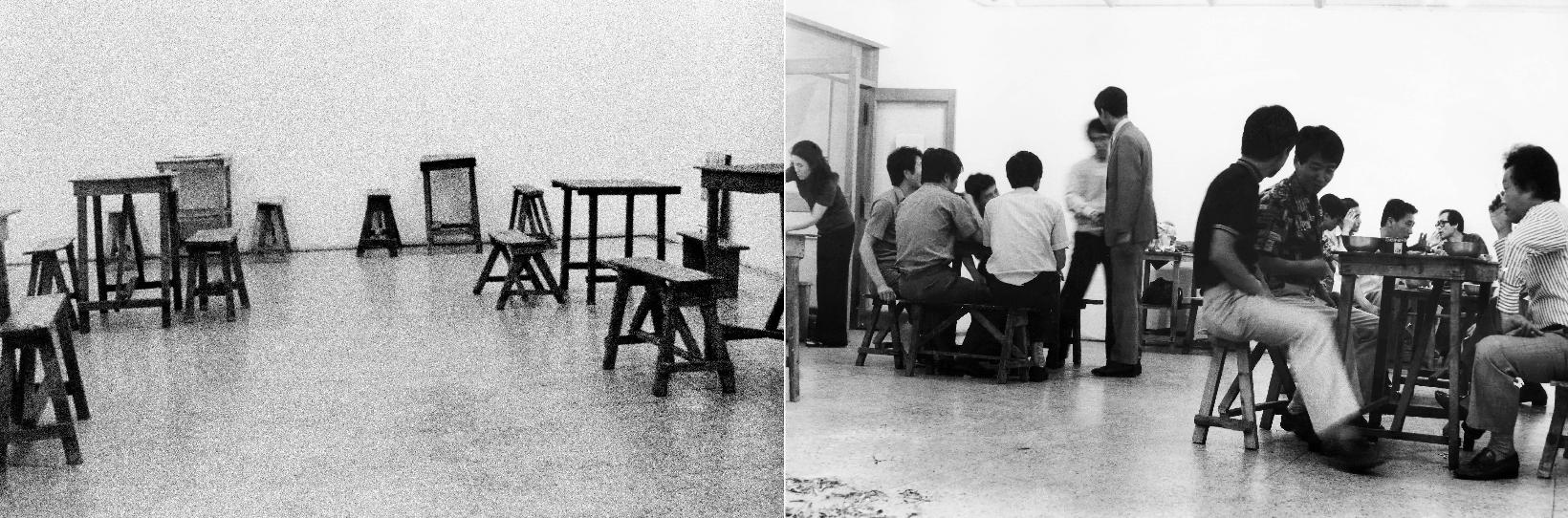

One day, I visited a bar in the daytime to treat my senior at the university who came to see me. Although I feel the same now, but the bars at that time were intimate places like coffeehouses today. While exchanging glasses between two of us at a lukewarm bar without any customers except for us, my gaze stayed on the wooden table and chairs. It seemed as if I was listening and seeing the sound of many people and an illusion full of smoke from cigarettes. The traces of rubbing off countless cigarettes on the table and chairs, burnt marks made by hot pots, and incessant mopping by the worker at the bar–all these seemed to make noises together. But all of this disappeared at once. I was there, and my senior was sitting in front of me, but we were there and not there at the same time. I could not prove it precisely. I could not be my senior sitting in front of me, and he could not be me. The bar I was experiencing could not be the same as the place he was encountering. Where were we? That experience was so fresh for me, so I immediately bought a chair at the bar. But I felt it was not enough, so I bought all the tables and chairs at the bar and left them at a corner of my studio. That led to my solo exhibition. As a result, the goal of the work was to provide the audience with an opportunity to re-experience and reflect on our own situation that we had been mindlessly experiencing by separating an aspect of our everyday life into the gallery. The role of the artist is up to this point, and the audience will be free to participate the work and have time for one’s own experience that others cannot know. Looking back, I think that the realization of some works at that time was done out of luck. This is because these ideas linked to my latter installation works, sculptural pieces, and paintings.

You initiated the group ‘Shinchaejae(New System)’ and participated in A.G.(the Korean Avant-garde group) exhibitions as well as a few group exhibitions. In 1974, you established Daegu Contemporary Art Festival. Your traces can be found in historical and symbolic events in the history of avant-garde art movements in Korea, but Daegu Contemporary Art Festival is particularly meaningful as it is called as the starting point of Korean avant-garde art movement. What were the background of the establishment of the art festival and the direction of the art festival that you wanted to pursue?

As I mentioned earlier, my generation in the late 60s had strong enthusiasm in contemporary art and there were rigorous group activities to research and present contemporary art. The groups such as Origin and Muhandae(Infinity) already had artwork presentations, and the year 1970 saw exhibitions by A.G., S.T., and Shinchaejae. I formed Shinchaejae in the late 60s and participated in eleven exhibitions by 1975. I also joined exhibitions organized by A.G. in 1971 and 72. In the meantime, I thought the Korean art scene should be modernized more quickly by more rigorous practice by these group activities. However, the momentum was lost in Seoul due to the lack of cooperative relations in the art scene. So I moved between Seoul and my hometown Daegu to exchange with less than five artists in Daegu who were inclined to contemporary art and those in Seoul and other places throughout the country; working on a movement to spread contemporary art. In 1973, there was Korean Contemporary Artists Invitational Exhibition; Korean Experimental Artist Exhibition in the spring of 1974; the first Daegu Contemporary Art Festival in the fall of the same year; the first Seoul Contemporary Art Festival in December 1975, organized by Park Seobo; the first Busan Contemporary Art Festival in 1976, led by Kim Jong-gun and Kim Hong-seok; and the first Gwangju Contemporary Art Festival, led by Kim Jong Il and Woo Jaeghil; and the first Jeonbuk Contemporary Art Festival, led by Liu Hue Yol and Moon Bok-Cheol were held in cooperation with each other. The festival in Daegu continued for five years; Busan went on for two years; two years for Gwangju; and more than ten years in Seoul until the 80s. In addition, there were group exhibitions in different scales so that the artists in the 70s could continue friendly exchanges by travelling to different places in the country throughout the year. I think the period was an unprecedented time when such a big number of artists exchanged without the barriers of university-based factions or local communities, and it was a time when there was the most rigorous communication between artists. It had a huge influence on university students and their education, and it greatly enhanced the familiarity of citizens with contemporary art. I think the enthusiasm of all these artists came from the yearning to realize the artistic format that was intimate to them.

Photographed in 1977; Printed in 2016

C-print, 35 x 29.5 cm

Void, a work originally presented in the second A.G. Exhibition in 1971, fixated reeds growing along Nakdong River using cement and transported them to the exhibition. The work looked as if you moved the natural environment of Nakdong River directly to the exhibition, stirring the identity and structure of the space of an art museum. Seen as an extension of Void, the group performance art presented at the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Daegu Contemporary Art Festival under the names of happenings or events are also very interesting. Outside the exhibition space, how did nature influence the experimental artistic activities at that time as a stage and artistic materials?

Until the first and second exhibitions of Shinchaejae in 1970 (the group held two exhibitions every year for eleven times until 1976 as research presentations), there were works that had been heavily influenced by pop art. In the third exhibition in 1971, we considered ‘pop’ as a modernist remnant that did not fit us. So we broke away from it and took on new attempts. In the A.G. Exhibition in 1971, I presented a work that filled the exhibition space with a field of white reeds. The work accidentally reminded me of the reeds of Nakdong River that I went along from time to time when I was a child. It reminded me of the midst of the giant reeds that densely populated the field in the summer, the playful children tanned by the sun padding the waters in the swamp, and the dreary sound made by dry reeds rubbing against each other by the strong wind in one winter, which made me to think of myself wandering in some strange domain. The work was created by an idea that I would move the reed field into the museum although not exactly in the same shape, letting the audience walk through it. I am curious what kind of feelings and thoughts the audience will experience in another space filled with reeds. We are living in a world where we have to change the habit of seeing the world by simplifying it through concepts. After returning from the 9th Paris Biennale in 1975, I thought about what I had to do in the art movement. I thought that art in its all areas, which did not only include traditional genres such as two-dimensional paintings and sculpture but also installation, performance art, and video art started to form new history. I thought such influence had to extend their territories in the Korean art scene. So, at the 3rd Daegu Contemporary Art Festival in 1977, there was an additional ‘happening’ and event at Gangjeong beach along Nakdong River, outside the exhibition in the Daegu Citizen Hall. I think it was a meaningful attempt as the first occasion where dozens of artists presented their works. In the next year, there was a presentation of events in Naengcheon in Dalseong county, and presentation of performance art pieces by Korean and Japanese artists was held at Gangjeong beach in the 5th Daegu Contemporary Art Festival. I believe the art festivals since 1980 sufficiently fulfilled their roles. So, I have been focusing on my own work since then.

Looking at your works such as Untitled-75032 (installation piece with deer bones) or Becoming and Extinction (apple installation), one cannot but think about the meanings of ‘traces’ and ‘existence’ once again. The ‘traces’ and ‘existence’ that you brought into the exhibition space are connected to the images of ‘loss’ and ‘death’.

It is said that the traces, existence, and presence and nothingness are things that do not stop. If nothingness is materialized, it becomes a presence while a presence goes back to nothingness. Since the complete ‘nothingness’ or ‘presence’ cannot be realized, both are considered in a flexible manner in the Chinese philosophy and there are notions that substances are presence and nothingness. In Buddhism, the worldly things created by phenomena occurring under the conditions of causes and environments (緣起, dependent origination) are meaningless and empty. Lao-tzu suggested that we should practice Wu wei (無爲, non-action), the way through which nature operates, in the human society. Modern physics tells that even if a human being dies and disappears, the elements remain unchanged and remain with the universe. All these discussions are that all elements of the universe are functioning in an organic relationship.

You once said that you wanted to have a direct conversation about your works Untitled-75031 and the ‘pheasant’ piece. Looking at your works at that time, it seems that there were many cases where your works used animals and plants either they were dead or alive. Why did they become the subject of your work?

In the case of the pheasant piece, there was a stuffed pheasant from a specimen room that had been kept at my studio for still life paintings. I placed the stuffed pheasant and drew traces of footprints on the floor, and it showed that it moved along what I had drawn. At that time, I thought that anything around me could be the subject of my work. However, I had serious questions about the languages of being or existence.

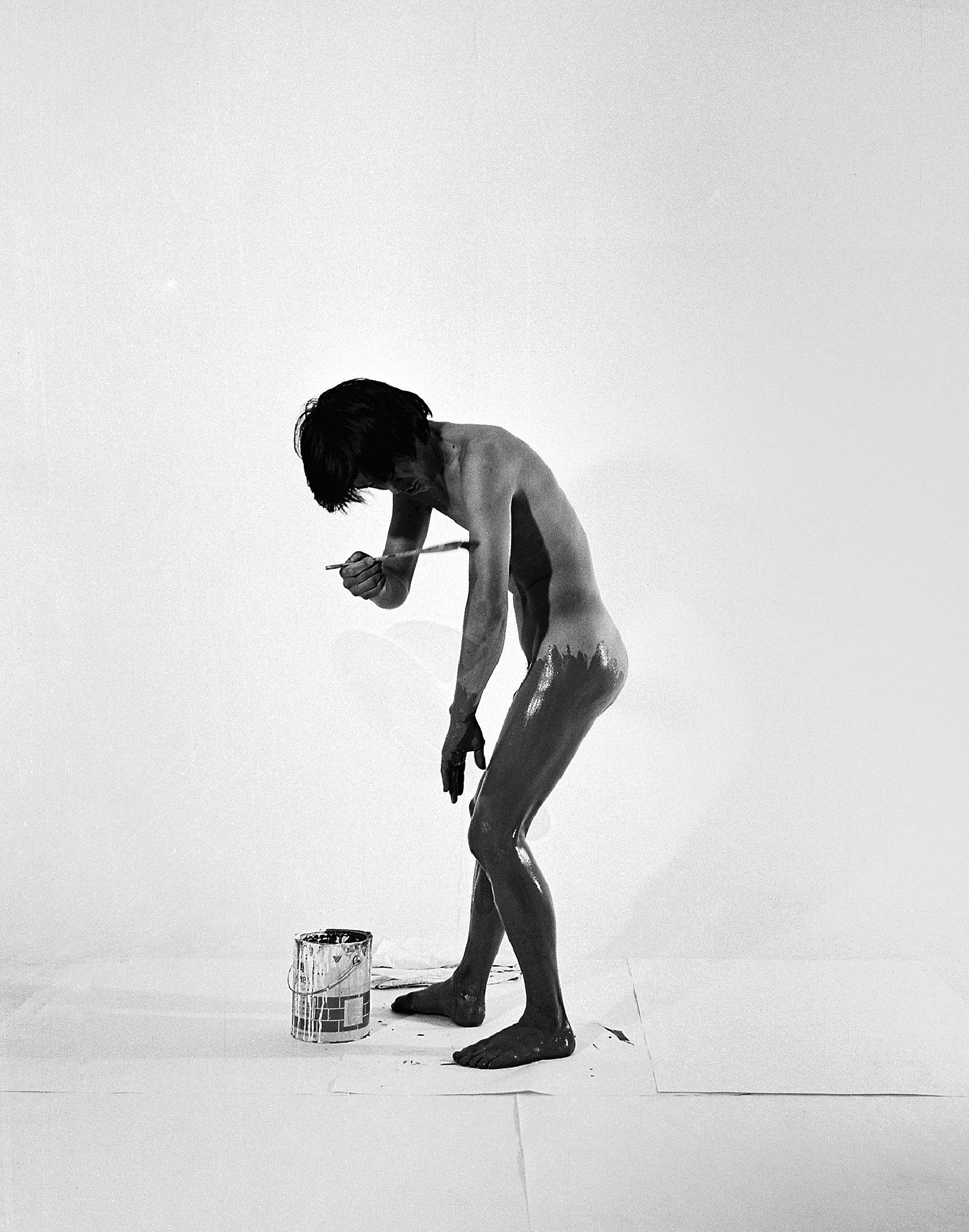

It seems that Painting(Event 77-2) is a work that best reveals your anguish about ‘existence’ and ‘traces.’ You painted your body and wiped the paint with a canvas cloth. You then drew circles around the remaining cloth. Your thoughts on existence that you must have felt through your skin in that process, and the experience of the audience that would sense your presence through the photo documentation and the cloth… Furthermore, this work can be considered as a performance, photography, and sculpture, but it is also confronted as a painting under the context that you ‘painted’ the paint on a flat canvas. Did you perhaps reflect your thoughts on the flatness of ‘painting’ in this work? How did you first start this painting performance and how did it influence your subsequent paintings?

Painting(Event 77-2), or so-called the ‘nude performance’ was done with ease and lightness. It was done with an idea that how easy and tactile a portrait could be, if it is not done by a traditional method but by wiping out a canvas cloth, and so it was done as a performance after renting a photo studio. While organizing documentation recently, I found out that the work was done in 1977 and it was exhibited at Seoul Contemporary Art Festival in January 1978 (held at Deoksugung, the National Museum of Contemporary Art [now MMCA, the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art]). And I experimented with the new painting that I was thinking about in 1975 with basic studies of the canvas cloth and images. Then while I was spending a few months in Paris to participate in the Paris Biennale, I was convinced that it would be possible to interpret the traditional forms of painting and sculpture in a new contemporary way. I have been exploring about painting until now and experimenting with sculpture since 1981. If my installation work comes out of organic relations, I think my painting and sculpture are also related to organic structures.

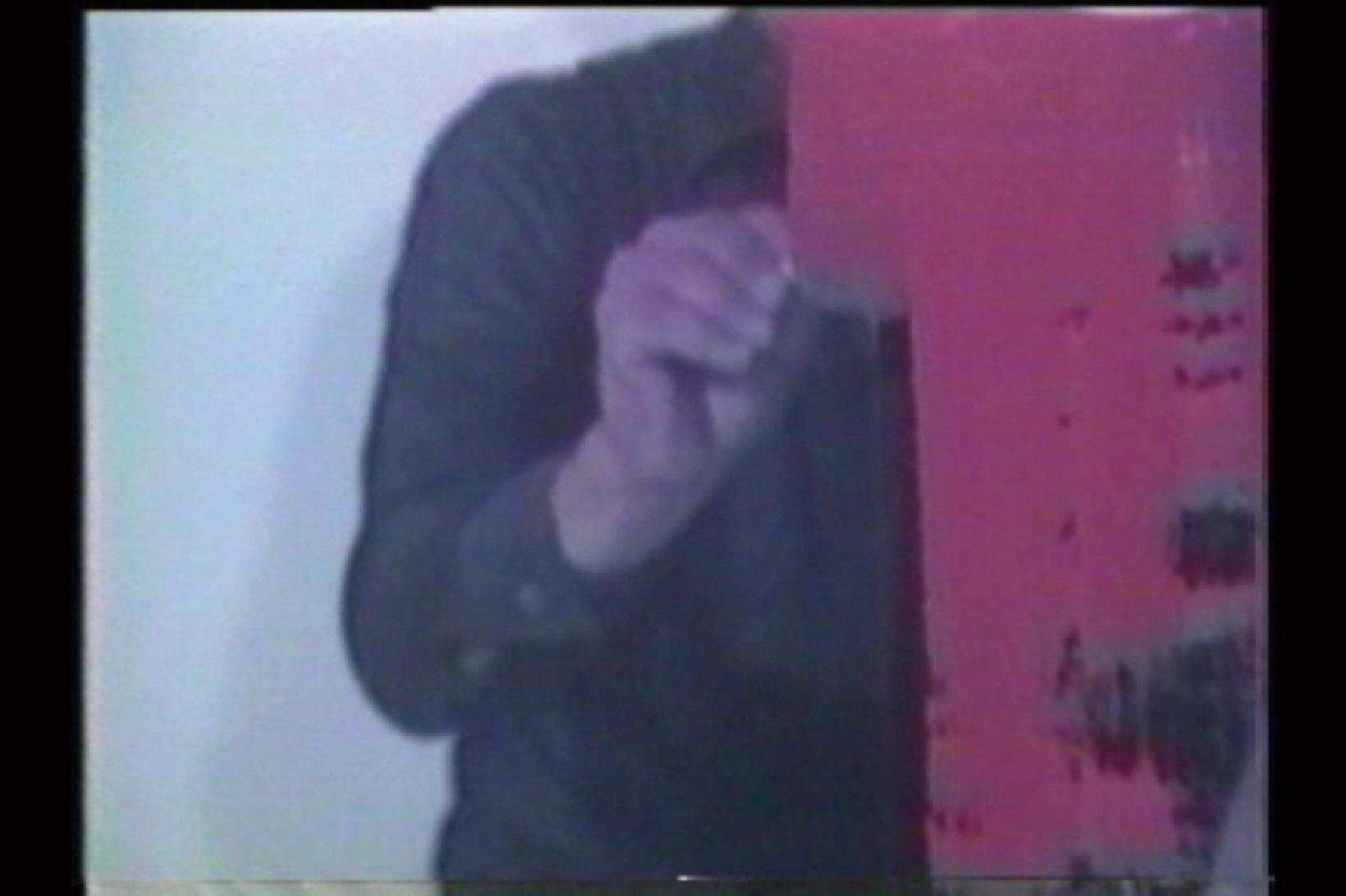

Your work is not limited to one genre but is developed in various media such as performance art, installation, video, photography, sculpture, and painting. What made you have an interest in video art, which was not common in Korea in the late 70s?

After participating in the Paris Biennale, I also believed video art that was developing its history and different works were expanding the genre. In 77, I piloted a video work, Painting at my studio. After that, I borrowed a photographic studio called K-STUDIO to produce my work and other works by my colleagues. In the next year, with my companions, I exhibited my work at the 4th Daegu Contemporary Art Festival (held at Daegu Arts Center). I am also a beginner in photography. Camera is a machine but it is a rare instrument which we can see the world through the eyes of others. My hope is to approach the world with a different perspective, by having a completely different medium from our views, but it seems it is not easy. In 2006, I exhibited my photographs at my solo exhibition at the Musée des Arts Asiatiques in Nice, France, and I occasionally presented some of them in my solo exhibitions. However, I feel pity that I just have a few occasions where I can focus.

Could you mention any essential artist or work that should be remembered, created in the process of various contemporary art movements in the 70s?

I think that now we have to put an effort to break free from the Western and modern ways of thinking, and develop our intuition by combining the wisdom of the East and West. Our work will then be more accessible in our own language. In the 70s, young artists created a lot of passionate works in a difficult social environment. Possibly because of that, sadly there are many artists that passed away too early. Many of my colleagues, including Lee Dong-youb, Lee Hyang-mi, and Kim Jin-seok passed away, leaving their good works behind. You can see they are that are keeping their health are still producing works excellently. Kim Whanki’s work, which was awarded at Hankook Ilbo Grand Prize Exhibition, was an abstract painting made of dots that he had been working on in New York. I felt that the dots in the painting did not belong to anyone but to the artist. I think that they carry emotions that formed the artist, which are full of the long journey in the artist’s life. I would like to call it Qi (氣) or energy. Such energy is something mysterious that one cannot imitate. I think that energy fills the universe, but it reveals itself in this way in our work. I think Kim Whanki is communicating with us with warm and pure longing. At that time, the work gave a fresh shock to the Korean art scene. He put his artistic form that he had formed through difficulties into a field of communication. I would like to talk about artist who is senior to me in a way that I feel. There were artists one generation earlier than my generation who participated in contemporary art festivals in the 70s and built their own painting styles. Yun Hyong-keun was among them. Regarding the artworks that were being called as contemporary art, for artists in earlier generations, most of them transformed their styles into new ones around the 70s. Yun has maintained his style for over forty years since he had established it in the 70s. He creates bold forms on the raw canvas, often symmetrical but sometimes in a simple square form, geometric yet possibly reminding of the landscape of empty mountains or hills. Those images make us revolve around an area that we cannot easily comprehend. The color is not light but gradually subdues. I feel his heavy stubbornness in the deep weight of colors. I think the hidden secret of the charm that has kept the strong vitality of his work for a long time lies in the smearing and spreading of colors into the canvas. The smearing and spreading were not exposed conceptually but achieved by the beautiful harmony of his aura and the spreading of colors. I think his life was led by paintings thanks to this work of temperance. I gave examples of two artists, but I think that if Korean art is gradually accumulated in this phase, a good history will come out of it.

This interview from the exhibition catalogue of Lee Kang-so : Disappearance at Gallery Hyundai.