You did your first exhibition in 1991 when you were twenty-six years old. The 1990s was a period when the Korean art scene experienced many changes. At the end of the 1980s, many people went abroad to study or travel as the ban on overseas trips was lifted. However, many people had to come back to Korea while studying overseas due to the financial crisis in the late 1990s. In the art scene, it was a period when diversity came into play as alternative spaces emerged and Western theories such as postmodernism and pluralism were mentioned by the many. You must have had a lot of thoughts on the limitation of the traditional Oriental painting and its change as an artist practicing the genre. You highlighted the word ‘everyday life’ when you organized a group exhibition in 1995. It’d be good to know the circumstances of the exhibition.

There are many difficult parts in your question, which makes it difficult to clearly point out and explain. It seems true that Korea has gone through fast-paced time and very complex periods. Looking back, around the time when I graduated from university, there was already a situation where the Oriental painting scene was feeling bored with ‘Koreanness’ or ‘traditionalism’ but could not find a way to overcome them. The situation of the art scene in general was, since postmodernism was shaking the Korean society, I could not help but think seriously about how my work could survive the situation. At the same time, I did not want to move away from the materials or substances I was dealing with, so the works produced in the middle of my career were trying to find the power and potential of materiality that I was working on. For example, the reason why I came up with the theme of ‘everyday life’ was not just to examine the visual change of the world in which we live but also to raise a concrete question about the conventional attitude of Oriental painting… The aesthetic terms such as ‘Qi Yun Sheng Dong’(氣韻生動, dynamism and movement filled with energy) or ‘Gu Fa Yong Bi’(骨法用筆, heaviness and lightness of brush stroke) that had been used for a few hundred years could not but face new interpretations corresponding to the changing times. ‘Everyday life,’ the theme I raised, could be a story about a certain reality. Or it could be an attempt to come up with a concrete methodology that responds to the question, “How a certain attitude and experience about the fundamental points of objects can become a painting?” It was to say that, when we talk about the beauty of a tree, we do not just think that it is beautiful as it is but ask a question about the beauty itself. So, it is not a concept that tells, “This is the energy and dynamism of a tree. You thus have to reach the tree by diligently exercising brush strokes.” It rather starts with a question, “Why is the tree beautiful?” I now think that it is an interesting part. For example, it is interesting that a painter does not focus on the object itself but a certain ‘space’ between an object and the painter that looks at it. I think that the ‘space’ is where countless possibilities are generated. This I think is the point that largely differentiates itself from the existing methodology of Oriental painting.

I was impressed by your definition of Oriental aesthetics. You mentioned, “Oriental aesthetics is a language of the body,” talking about the ‘attitude’ of a person that practices an ink stick, not the ‘spirituality’ that is reflected in the material. I think that it excellently connects to the fact that you brought ‘everyday life’ as your subject. Since it is a language of the body, and each body has different aspects. So, to show objects that each body encounters and interacts with in the world, one cannot but start at a place that is the closest to his body. Then, spirituality also starts from ‘everyday life’ that can ultimately be interpreted through one’s ‘language of the body.’ To describe each work produced at the time, how did your works such as the one that you continuously painted while you were observing the death of your grandmother, Subway, and The Scenery Outside the Window connected to the concept? I think that an artist’s idea reveals itself more or less in the end.

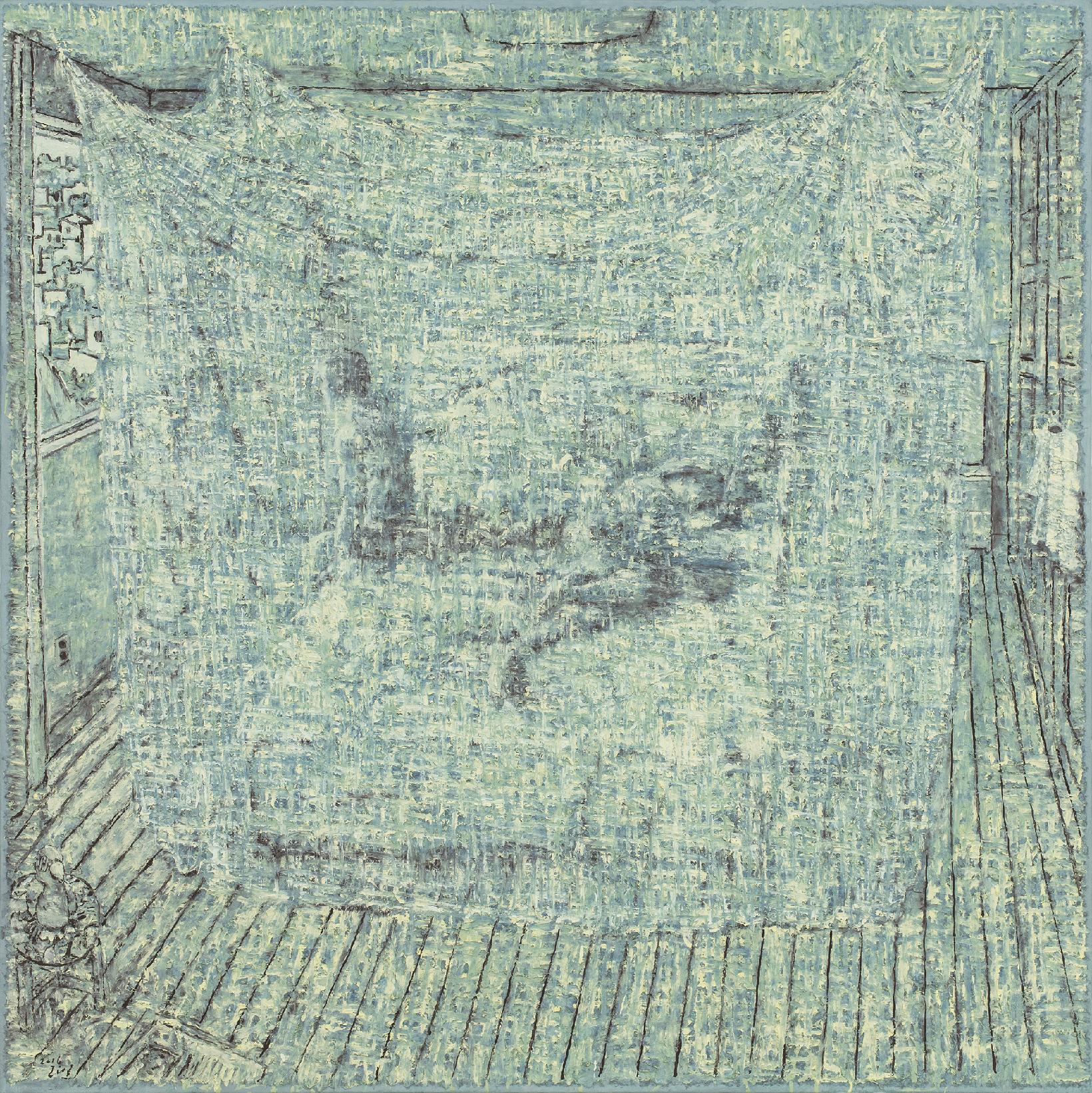

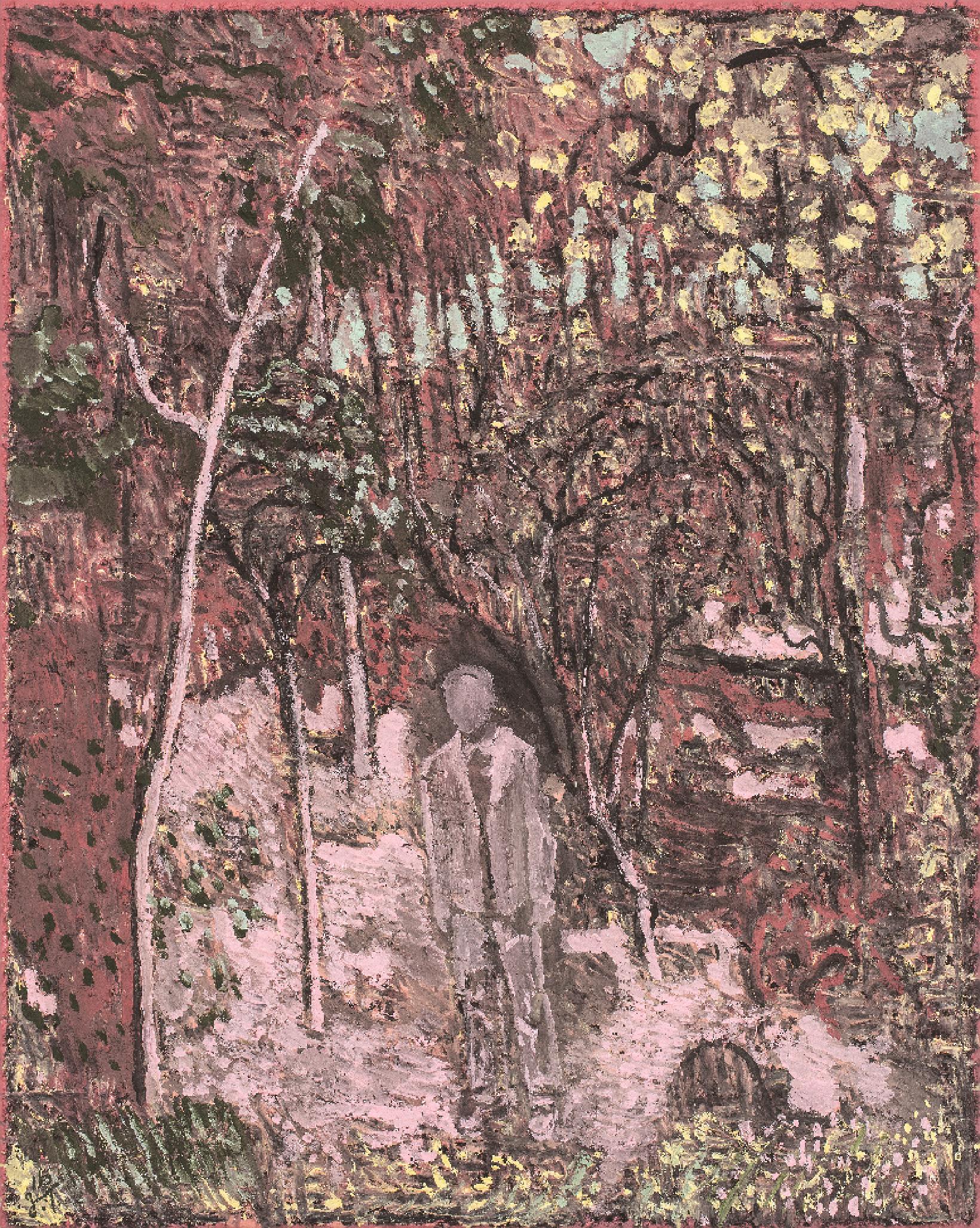

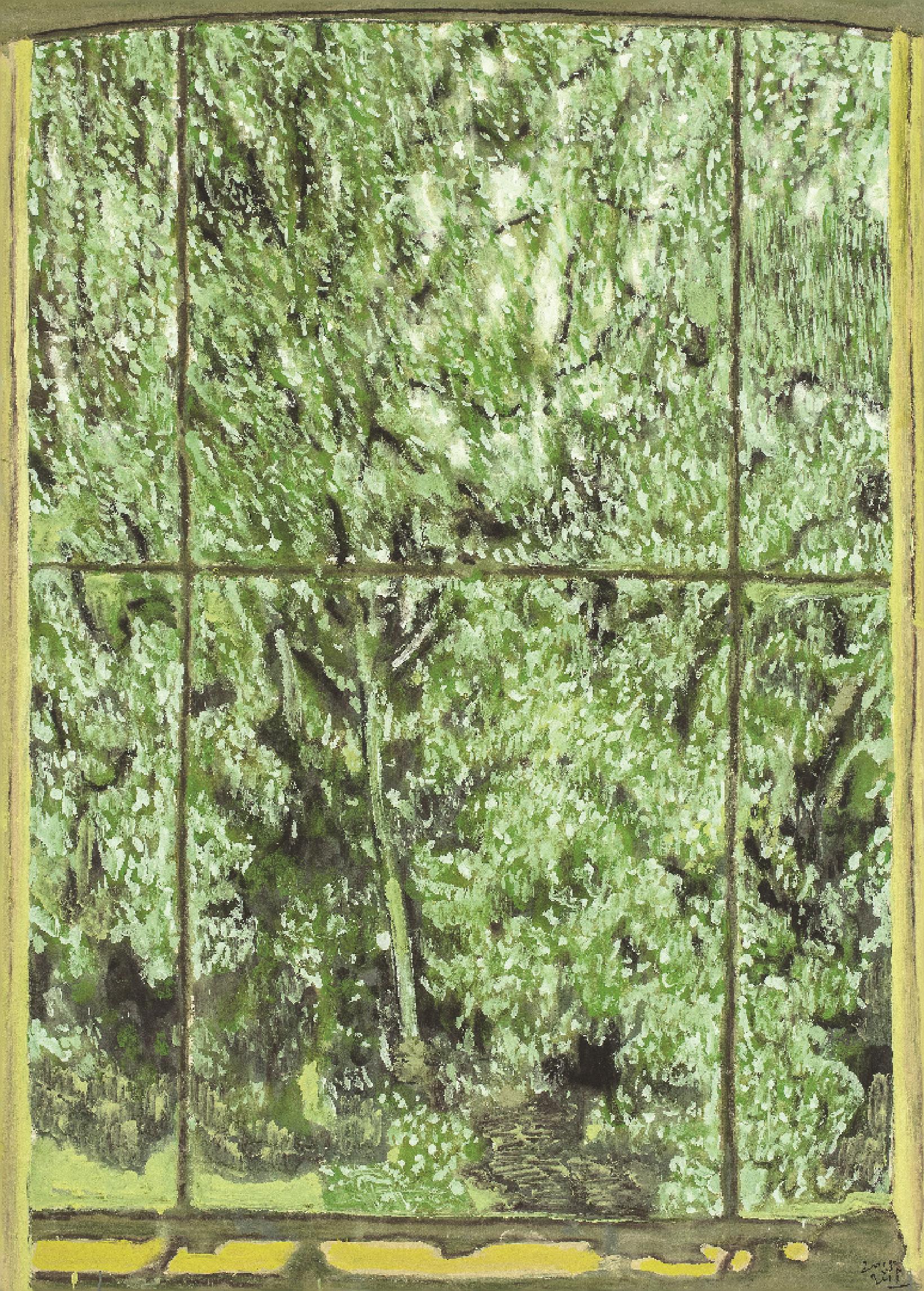

You’re correct. It was when I was creating drawings in my grandmother’s room for about a month before she passed away that I saw the possibility of ink painting. I felt that ink painting could not only capture the atmosphere of my grandmother’s room, her breaths, and the sound of her moaning as concrete painterly motives but also become a certain figurative principle. It was a very important experience. However, it was in 1999, which was about four years later from that moment, when the questions raised by the method of accumulative drawing and its formal presentation was corresponding to each other. That is to say, I felt that “I could become a more concrete work,” feeling that things that were close to me could be expressed as a painting in a more fundamental manner while I was working on The Scenery Outside the Window. Of course, Subway series also contains a lot of drawings. This is because that to make a drawing is to continuously ask questions. I think that I developed a methodological proximity with drawing as I was accumulating such works. Maybe, that also generated some stories around such a practice.

You constructed a curved wall for the Korean Young Artists exhibition in 2000, which was a very rare way of composing an exhibition space at the time. (Yoo: Yes, I asked the museum to make the wall in a round shape.) Your The Scenery Outside the Window was presented as if it was a scene from a movie (Yoo: It was The Long Fence series, not the The Scenery Outside the Window.) Well yes, so you used the term ‘scene.’ In the end, you inserted the time of the landscape you were depicting, which was to insert temporality. (Yoo: It was a landscape that was different from the usual notion of landscape but the one that was embedded with a certain event. It was also depicting a certain scene, as I explained it as a ‘scene’ in a bit cinematic sense.) It was a landscape where an event was combined with temporality.

The reason why I asked for the wall to be in a round shape was maybe to extend the resonance of time from the six works from the series The Long Fence. In fact, I first wanted to complete an enormous three-meter wide piece. However, I somehow could not complete the work and it was realized in the form of six works that stretched wide. I was quite satisfied after completing the work. Above all things, I came to think that my painting was somewhere between cinema and painting. After then, A Scene became a painting that continued to appear in my work as part of the title for a while. In fact, I produced an animated version of the work ten years later for an exhibition Flare: A Brand New Start in Art that took place in the former Defense Security Command site (which now became MMCA Seoul). It was a very interesting work.

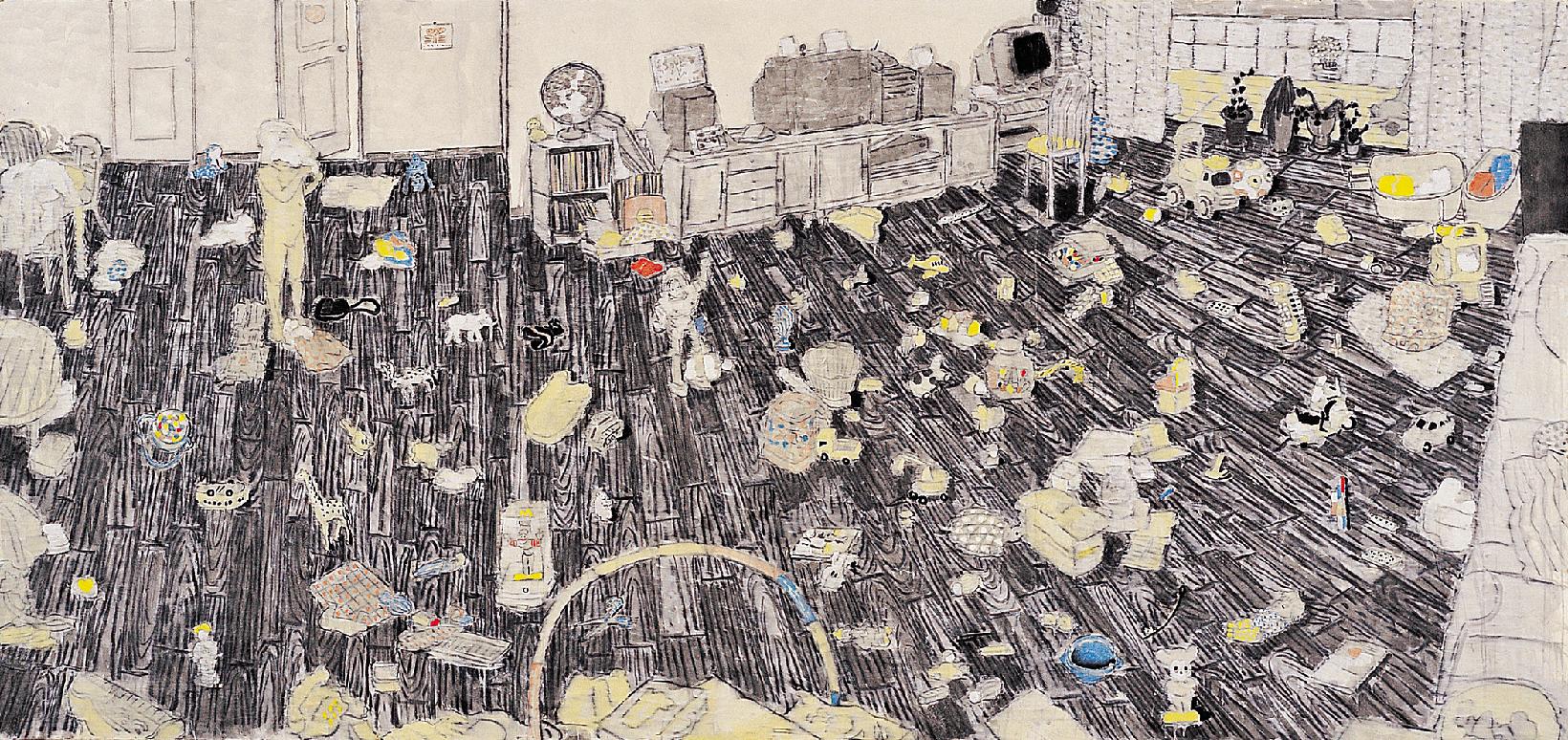

Looking at your practice, I see that you continued new experiments from the late 1990s until the early 2000s. In 2002, you presented the landscape of apartment complexes in the exhibition A Puzzling Routine at Dongsanbang Gallery. I read in the text that you moved to an apartment complex when you moved from Ilsan to Hongje-dong in Seoul in 1999. Was it when you married? A Puzzling Routine series was produced after you had your child. I felt that the landscape composed of apartment complexes was very ordinary yet unusual and novel. It also seems that the series occupies an important place in your practice - I think that the landscapes of the exterior and interior started to coexist since this work and concepts that are more invisible entered our real life. Can I say that you narrowed the perspective down? It was not to deal with everyday life merely as the subject of my work but to absorb the change of the external world entirely. It also seems to be connected to the notion of ‘the skin of life’ that you have mentioned. There were many changes. Marriage, child, things done by friends, the apartment complex that you were residing, the landscape of the apartment complex seen through a window, among others.

But the apartment complex is a space that is difficult to deal with using the technique of accumulative drawing. Because it is plain, without many figurative elements, and there are not many spots to use brush stroke, it is a pitiful space. To solve the difficulties… I think that it was possible after The Scenery Outside the Window, thanks to the trembling surface of the painting as different materials such as paper, ground shells, and ink stick, and also the technique through which I could accumulate the depth of ink and power, creating a difference between layers within a painting. I could transition a painting to a matter of a kind of ‘emotion.’ It could have been very boring without doing so. The space inside the building let me create more psychological and emotional works, which were looking more deeply into the inside of life. With the change of life, I could naturally broaden the width of the practice.

Since you paint narrow space inside the building, you show a quite radical style. The floor sometimes vertically stands up, and the pattern on the floor often stands out. A critic Ko Chung Hwan once mentioned about such composition and repetitive patterns, “(These) seem similar to the surface effect of modernist paintings and their repetition, patterns, and reductive features.” I thus think that it was a moment for you to radically transform your practice, overcoming the formal characteristics of the existing Oriental painting.

I assume that it was inevitable. I was changing... And I think it is proper not to say that I was transforming the existing format of Oriental painting but expanding its possibilities.

You stayed in the United States for a year during your sabbatical in 2011, and I guess your everyday life shifted a lot due to the change of the space you lived in. Could you explain your work around that time?

I think I was devoting all my thoughts to an exhibition at Gallery Hyundai, which I would have to do after returning to Korea. Leaving Korea and working outside the country for a long time was a very valuable experience. I thought that landscape seen from Korea and the United States differed a lot. You can feel the difference between the ten pieces depicting windows that I produced in the States and the previous paintings depicting windows in The Scenery Outside the Window series - you can feel that the ones I created in America strongly present materiality that their colors and the touch of brush confront and encounter the windows, which I think was possible since I created them in that country. And I could also think about the unfamiliar experience of staying at a place while I was spending one year in the enormous country. More interesting was that I could reflect on how unfamiliar the Korean society and its landscape were after coming back from America.

Where did you stay when you were in America?

In New Jersey. It was a quite rural town.

You painted many interior landscapes then, too?

I did many interior landscapes. Because they were what I was seeing. Painting the natural landscape was a bit tricky since the visual feeling of nature there was fairly different. I needed more time to connect my body to that landscape - so I painted the interior landscapes, especially ones where my family were mingled up with each other or scenes seen through windows, which were possible for me to paint at that time.

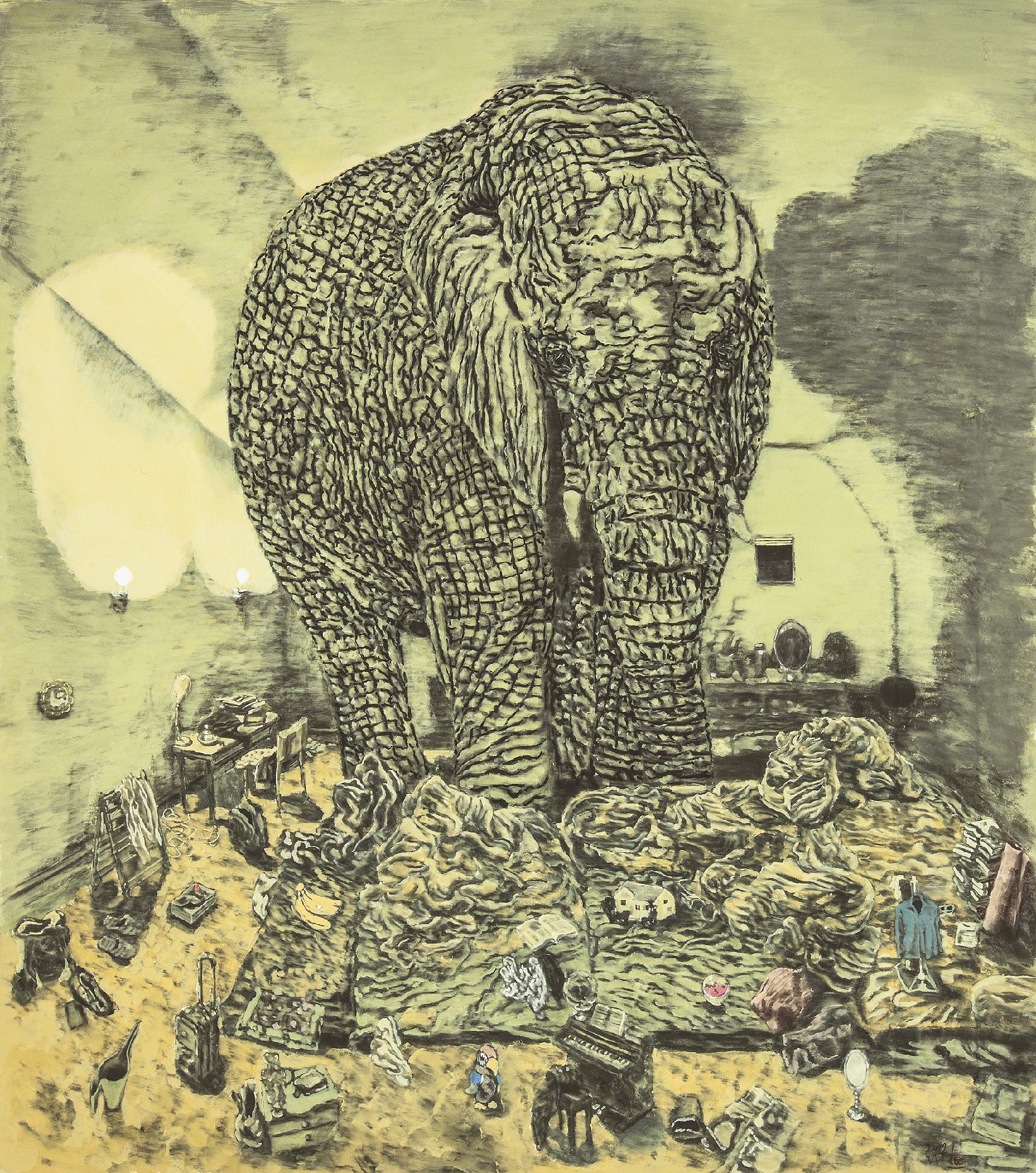

The interior landscapes you created around the time feature an elephant on a bed, a puddle made on a bed, water splashing around it, or a bed with waves of water, which all show diverse imagery.

I observe foreigners when I visit America or other places nowadays, and there is this absolutely strange feeling I feel from people. This is the theme I want to work on one day... But I had this feeling when I was in the States, too. Especially that three different families from a small country were awkwardly living together in one house was of much interest to me. And I had a feeling that America had already become old as it was staggering with its politics and economy. Actually, I wanted to come up with a scene where an enormous giant that is too big to make any movement in my room while it reads a newspaper, but I failed to do so. The piece that depicts an elephant was a result of an attempt to alter the giant in the failed piece I tried in America with a baby elephant. I am fairly satisfied with this work.

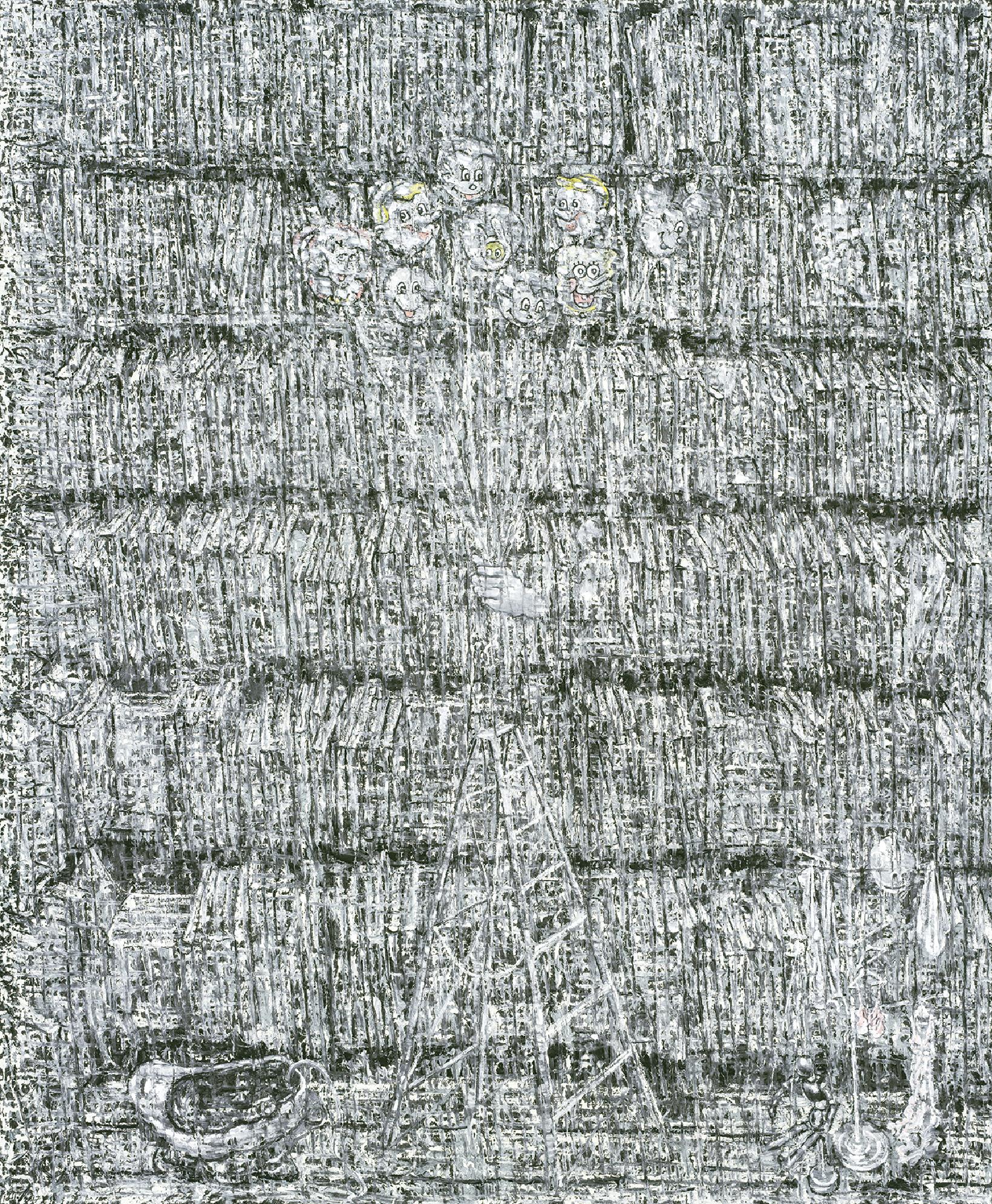

I cannot take my eyes off from your work that depicts your self in a shower. I felt that your paintings of yourself in a shower were very unique. I think I have almost never seen an artist that depicts himself in a shower.

David Hockney was good at painting men in showers. And there are many artists that depict people in showers, including many German expressionist artists. Hockney was very good at depicting showers. But my paintings depicting men in showers was not initiated by Hockney’s paintings. It was in fact started by the sense of fear I had when I took showers. It was the moment when I turn on the shower, the moment when my body very much feels a lot of tension. Bill Viola also has a video about a cold shower room and water. I sometimes experience moments where all different thoughts are mixed. I thought a lot about this - So, how can I draw that feeling with my painting? I had many ink paintings, but they were not enough. But I could not satisfy myself. So, time passed and the work could be completed in 2004 when a certain methodological issue was resolved.

2009

Black ink, white power and tempera on Korean paper

180 x 177 cm Inquire

2017

Black ink, white power and tempera on Korean paper

244.5 x 203 cm

You consistently produced paintings depicting showers - in 1998, 2004, and also until recently.

I have so many ink paintings. And I have many paintings that are not yet exhibited. I painted a few works after 2004.

In your work, there are many images of ‘water.’ A painting of a ‘fountain’ is one of them. It is the one that depicts water going upward, which in the end goes downward. It is very interesting to me to see how the work changes over time. It seems that the expression of water that waves as if it is alive becomes increasingly natural and the looks of moments when it is scattered by the wind are exquisitely expressed.

I first started working on the fountain pieces around 2001 when I was a lecturer at the Korea National University of Arts. There was a pond that might have been made by soldiers (** Korea National University was formerly a site used by the Korean Central Intelligence Service) and a fountain that spurted three streams of water, which were part of the place that I often sat down during lunch time. Is it still there? It might have been gone now. I sometimes discovered fairly interesting scenes while sitting on a bench there and looking at the fountain, and it was also an entertaining experience to observe and make drawings of a scene where water streams create unexpected vibrations within the landscape, disassembling and cutting it into pieces. That’s when I started producing fountain pieces. Then, I made a drawing of a water fountain in front of Changgyeonggung Palace and exhibited another fountain piece at Savina Museum, and I will present two or three fountain pieces in the upcoming solo exhibition at Gallery Hyundai. In fact, fountain is a very unfamiliar subject seen from an Oriental way of thinking. The Oriental philosophy of water led to the observation of water that follows the laws of nature, depicting a lot of waterfalls. However, it might seem rather new to see an Oriental painting artist depicting fountains. It is because people think about painting waterfalls, not fountains.

Bill Viola’s video pieces pulls water in and let it fall and put it back and use it in a free and bold manner.

But it is difficult to have such a way of thinking with an Oriental mindset.

In any case, your fountain pieces had certain feelings like some dazzling landscapes that make one feel moved and feel empathy. Your works that will be presented in the upcoming exhibition include new attempts such as paintings that emphasize uneven surfaces by layering papers with thickness. Looking at these works, one might feel that space increasingly becomes condensed? They give a feeling that everyday life and landscape gradually become united to become flat, permeating and imprinting each other. Since it is a work that you try anew, there might be some connections with or differences from your previous works.

Though different people might feel differently, I think I came to have more possibilities to push myself into the paper while I produce new works. After the solo exhibition at OCI Museum in 2014, I thought that I needed some change in my work. Can I say that I was requested a certain new order? I had a chance to rethink about the act of painting itself. While I was preparing for the exhibition at OCI Museum, I painted with much pain. There was Sewol Ferry incident ... The exhibition at OCI Museum indeed devoted much of its content to the sinking of Sewol Ferry. The incident happened while I was painting mountains and waters, which inevitably led me to reflect it to my painting of mountains and waters. It was the same when I painted woods. While I was working on landscape around the time of the sinking of MV Sewol, I could then understand a line from an essay that I had read in the Korean literature textbook where the writer looked back on a lecture he had given in a foreign country, telling that he could only remember that he said “The sky in Korea is dazzlingly blue and beautiful.” I thought that Korea went through radical changes, and people might have been in need of comfort from landscape. Thus, I think I asked a question, “How can a painting soothe a landscape?” For example, “Can I paint a tree as if I was soothing the landscape?” That was what I was thinking. After the exhibition, I thought that my paintings needed a more fundamental change. So, when I went to an artist residency in Germany for a year to spend my research year, I did not bring any material. I only took papers, and I think that I wanted to change myself again and again by purchasing all the materials in Germany and work with them.

You said that you went to Germany for a while in 2015? You must have visited many museums and saw many German paintings.

I saw many of them. As you may well know, German painting has a long history and many good works.

When you had a solo exhibition at OCI Museum, it was impressive that you created a space where people could enter only by bending their heads down. I realize that there were many intentions. I’d like to hear more explanation about the new work that you present in the upcoming exhibition. It is a work that you put layers of paper in thickness and beat them with a metal brush to sharpen the texture of paper while composing an image. I want to hear about the production method and its content.

The most significant context of the exhibition contains a lot of the notion of ‘a certain stroll.’ In a way, I would like to compose the whole exhibition space as a path for a kind of intellectual stroll where one looks into oneself, the landscape, and the times of our days that have passed. I am already curious about how the works, which push the preciousness of every moment of our lives that we feel and live through into the structure of paper, will be interpreted. I don’t know how to name this technique ... I once tried to mix Oriental ink and shell powder to accumulate time in a painting. I feel that I can expand this aspect in a more direct manner now. It is as if I raise this paper that is less than two millimeters thick, crawl into it, and push my way through it. Can this be a proper explanation? I think that I feel a lot about the possibility of drawing strange gaps of layers or certain events by directly intervening in the space as I practice my work. I assume that this is a completely different approach to the existing ways of ‘drawing.’

Listening to what you have just said, I remember that Ki Hye-kyung’s essay for your previous exhibition at Gallery Hyundai also impressively explained the characteristics of your work where colors and pigments were agglomerated at the center of the image. Does that connect to such context?

I assume that they are connected with each other. But since I now talk more to the materiality itself, I think in terms of concepts, I can work with more expanded ones. I will have to see how it will go.

Considering the works that you explained so far and their formal characteristics, I come to wonder what meanings can the genre characteristics of Oriental painting or Korean traditional painting that are being used in the Korean art scene in contemporary times?

It is true that genre characteristics cannot easily be defined. However, we should also avoid making sections within itself by these characteristics. We may need to take a critical look at the art scene in the times that have passed through these points. I hope that the art scene will expand to more inclusive and horizontal discourses. I think that we need to put an effort in expanding the possibility and universality about how a certain language is possible and how we can communicate in the current period.

In fact, distinguishing different genres such as Oriental painting and Korean traditional painting comes as difficulty when the museum categorizes its collection. Artists nowadays work in diverse ways without the limitation of a particular genre, so there are many artworks that are difficult to categorize by their genre characteristics. We categorize them into painting and Korean painting. There was a dispute over the change of the name of a category into Korean painting, and it is still a sensitive issue.

I think that the term Korean painting can possibly bring about a tendency to restrain us in our locality. I see that there is a need to discuss this issue in a longer term.

It was a valuable opportunity to hear about your practice and other diverse stories about your work. Thanks for participating in the interview.

Thank you.

This interview from the exhibition catalogue of Yoo Geun-Taek : Promenade at Gallery Hyundai.